Articles

Autonomous Vehicles: Ownership vs. Subscription Models

Autonomous vehicles are the way of the future, but the jury's still out as to whether their proliferation will be more in an ownership or subscription model.

Autonomous vehicles are the way of the future, but the jury's still out as to whether their proliferation will be more in an ownership or subscription model.

One of the important developments of driverless or autonomous vehicles is the ownership model the vehicles will operate under.

The most familiar model is personal ownership, where individuals own vehicles exclusive to them. There’s also the subscription model, where you pay for access to a fleet of vehicles when you need one, but don’t own one. And then there are hybrids of the two.

Depending on the model, there are important implications for law, policy, and society at large.

The American Transportation Cycle

For many Americans, it’s only natural to think of owning a self-driving car. Our culture, transport policy, and development have presumed individual automobile ownership for nearly a century. The assumptions are baked into the expectations and lifestyles we lead.

Not only do people expect to be able to park for free at shops, restaurants, and other destinations, but local laws frequently require businesses, and real estate developers to provide parking — often in outrageous quantities.

All this parking helps push destinations farther from each other, increasing the likelihood of a person taking a car trip between them and needing a place to park.

This results in extra demand on roads, which leads to traffic congestion, which leads to road widening, which leads to speeding, which leads to a road hierarchy with feeders, residential cul-de-sacs and so on converging into arterials.

Then there’s the incident management — all the congestion makes walking and biking unsafe, so parents have to drive their kids everywhere, buy more cars when the kids get old enough to drive, leading to … more traffic and demand for parking.

It’s a vicious cycle.

Owning Autonomous Vehicles

But that leads to one of the appeals of self-driving cars: a way out of the cycle. It’s not the only way, but it does fit within the construct of our lives.

Tesla is perhaps the company most committed to putting autonomous vehicles in the hands of individual consumers. Their cars already come with features labeled as “autopilot” or “full self-driving” — much to the consternation of regulators.

Assuming self-driving technology achieves its potential, it may filter down. Corporate and institutional buyers, along with wealthy individuals, will be the first to purchase, and as the technology matures and older model cars with it go on the resale market. Like with any other durable good, people will decide for themselves if they want to purchase.

However, the high tech world and the world of conventional property rights has been in something of a collision recently: companies are increasingly making it difficult to repair the machines they sell — either by design or by arguing the software is proprietary, so any changes, repairs, or reselling violates their patents.

While President Biden recently signed an executive order promoting “right to repair”, the precedent is still there and it’s possible automakers could develop a mobility-as-a-service model of their own, leasing vehicles to people.

Autonomous Vehicle Subscriptions

Uber and Lyft represent the field of mobility companies interested in reducing their labor costs by operating fleets of self-driving cars.

Filings have repeatedly shown that Uber’s current business model is not sustainable — drivers don’t earn enough to cover their expenses and the company isn’t turning a profit, either. A fleet of self-driving cars would, they think, bring costs down.

Institutions represent another potential buyer.

Some corporate and university campuses can be large and spread out enough that a number of circulating self-driving cars could find a lot of passengers. This would be especially useful for people running late to meetings or class — put on the livestream in the car and not miss anything.

Public transportation agencies may also be interested in driverless cars. Some already contract with ride hailing services to handle some paratransit services, but an autonomous vehicle fleet could help agencies provide good service coverage to suburbs that traditionally have population densities and layouts that inhibit transit usage.

Ultimately, there’s no reason that all of these can’t find a place in the future — but not everyone has the same impact on society.

Evaluating Autonomous Vehicle Usage

If autonomous vehicles merely replace automobiles at a one-to-one ratio, we’ll end up in a situation no different from now, with streets and highways full of cars.

There may be less need to park, as cars can resume moving after dropping off passengers, but on the other hand it seems unlikely that people who own their cars are going to let them circle and use up fuel or electricity.

However, a situation where ride hailing services own fleets of self-driving cars isn’t necessarily any better.

While it is true that one inefficiency with contemporary cars is that they are idle much of the time, and a ride-hailing service-owned autonomous vehicle would be able to be redeployed after each use, the problem is that, traditionally, a large number of people are commuting at the same time.

So the problem remains that only a certain number of cars can occupy space on the road at the same time. The fact that they are driverless doesn’t change that; vehicles will be constantly braking or accelerating to reach their passengers’ particular destination.

As such, it is important for government officials and consumers to understand the limitations of the technology.

There is no magic bullet for solving the complexities that come with American transportation system; however autonomous vehicles can be a balm. Whether it manifests more through ownership or subscriptions, time will tell.

NEWS

Recent Announcements

See how public sector leaders succeed with Urban SDK.

Company News

Urban SDK Joins Government Technology’s AI Council to Help Shape the Future of AI in the Public Sector

We’re proud to announce that Urban SDK has officially joined the AI Council, part of Government Technology’s Center for Public Sector AI

Company News

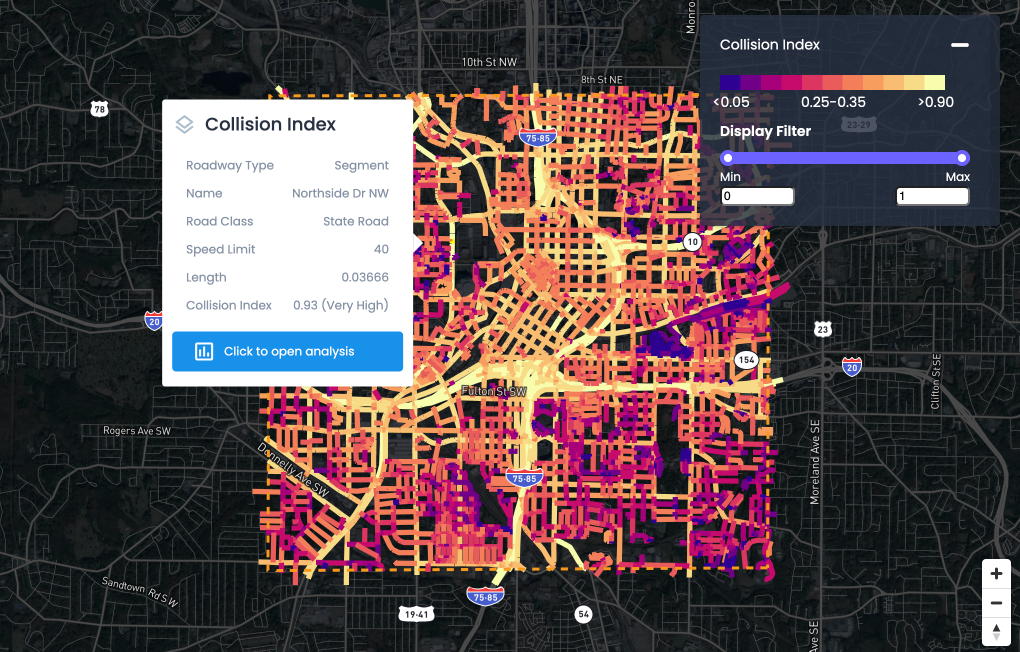

Collision Index: Proactive Traffic Safety Powered by AI

Communities now have another layer of road safety thanks to Urban SDK’s Collision Index

Customer Stories

University of Florida Transportation Institute Partners with Urban SDK to Expand I-STREET Program

Urban SDK and the University of Florida have partnered to expand the university's I-STREET Program

WEBINAR

Identify speeding and proactively enforce issues

See just how quick and easy it is to identify speeding, address complaints, and deploy officers.