Articles

Total Disruption: Autonomous Vehicles, Safety Regulations, and New Policy

The disruption caused by autonomous vehicles carries all the way to safety regulation.

The disruption caused by autonomous vehicles carries all the way to safety regulation.

When Elaine Herzberg was killed by a driverless car being tested for Uber late one night in Tempe, AZ, in addition to the tragedy of a life lost, issues of safety and regulation were brought into sharp focus.

After all, autonomous vehicles are supposed to be better than humans at driving and, therefore, should be able to avoid hitting people.

In the wake of such a crash, such jumps in logic have been reconsidered.

Autonomous Vehicle Safety

Not only do cities and state departments of transportation need to ensure that driverless vehicles themselves are safe, they must also consider the safety of pedestrians, cyclists and transit passengers. Ultimately, anyone sharing the roads with autonomous vehicles.

Currently, driverless vehicle regulations are left to individual jurisdictions.

Some states have passed laws, others use executive orders. The federal National Highway Traffic Safety Administration issued a Federal Automated Vehicles Policy in 2016, but as yet there are no federal regulations.

According to the Insurance Institute for Highway Safety, the different regulations for putting driverless cars on public streets range from allowing only testing all the way to deployment. Some states don’t require operators to be in cars, or even have licenses, while some don’t even require insurance.

Disrupting the Insurance Industry

According to Forbes, auto insurance is a $300 billion industry that will be disrupted when autonomous vehicles become commonplace.

Systems still requiring human input will retain existing insurance and liability structures.

However, insurance and liability for level five autonomous vehicles, those with no need for a driver, could fall with the company that sold the autonomous system.

“The very concept of driver or owner error disappears,” Nelson Mills wrote for Forbes. “If AI messes up and causes a crash, who is at fault?”

However, a driverless system failing to cause a crash is not the only way for an autonomous vehicle to crash. A human passenger could forget to clear snow off the windshield, resulting in reduced visibility, or they could throw garbage out of the car that hits another. There are plenty of variables.

Driverless cars will also interact more with pedestrians, cyclists, and other people not in cars, so addressing insurance and liability for those situations will be important for manufacturers and vehicle fleet owners.

Autonomous Vehicles and Cybersecurity

Another issue for insurance and liability centers on cybersecurity.

Autonomous vehicles may be vulnerable to hacking, malware and ransomware.

A compromised AV fleet could collect payment details from passengers and then engage in surveillance, or other nefarious activities.

Vehicle autonomy is based on the cars being connected to the internet. This V2X (vehicle-to-everything) technology enables an individual vehicle to process road conditions, along with the identity and proximity of vehicles, buildings, people, and anything else that make up roadways.

In the future, these systems may be extended and intensified through the internet of things (IoT), where autonomous cars will be networked to process what they’re seeing and also communicate with other vehicles, structures, and devices to further provide guidance and navigation.

As with any technology, this system could be vulnerable to cyber attacks.

“Because there are so many ways for vehicles to be connected, there are plenty of opportunities for a hacker to exploit vulnerabilities,” reported car website Motorbiscuit. “Hackers look for weaknesses or bugs in program software and systems to find a way in. Once they do that, they may be able to do a whole variety of things, from changing a car’s radio station to taking control of the steering wheel.”

A hacker wouldn’t need to take control of a car, though. A distributed denial of service attack could disrupt the vehicle’s connection to its servers. Ideally an autonomous vehicle in such a situation would be designed to have its hazards come on and brake to a stop. People would hopefully be safe, even if they ended up stranded on a highway.

Still, in such a situation regulations, or case law, will be needed to determine liability and settle insurance claims.

For example, if you’re riding in a self-driving car and the vehicle is hacked somehow and crashes, is the maker of the self-driving system, the vehicle owner, or the manufacturer liable for damages?

In such a situation, should passengers be required to have insurance the way drivers are, or does the owner/operator assume all the risk like a bus or taxi company today? Or would it be the responsibility of the self-driving system producer?

For automobiles, there was a pre-existing body of law and jurisprudence from ships, trains, carriages and other vehicles. For autonomous vehicles there is nothing yet.

Self-Driving Cars’ Trolley Problem

Another question that must be addressed is how autonomous vehicles will handle moral issues.

This is usually expressed as a variation of the trolley problem: a driverless car is traveling down a busy street when a person steps in front of it.

Should the car be programmed to hit the single pedestrian or swerve into numerous other cars?

As autonomous vehicles improve and continue to be tested on public streets, these are the sort of issues state and local regulators will have to address with manufacturers, developers, and automakers.

Forcing New Policy

A lot of early technology is often designed with the consumer thought of as an enthusiast trading stability for the early access.

Once market viability is determined, the new device or software is then introduced to real world tests and long term usage in order to discover bugs and vulnerabilities.

With autonomous vehicles, given all the safety elements involved, there’s too much at stake for a pro forma rollout.

Along with the new technology, autonomous vehicles — most especially self-driving cars — will usher in policy and regulatory changes as their proliferation continues.

NEWS

Recent Announcements

See how public sector leaders succeed with Urban SDK.

Company News

Urban SDK Joins Government Technology’s AI Council to Help Shape the Future of AI in the Public Sector

We’re proud to announce that Urban SDK has officially joined the AI Council, part of Government Technology’s Center for Public Sector AI

Company News

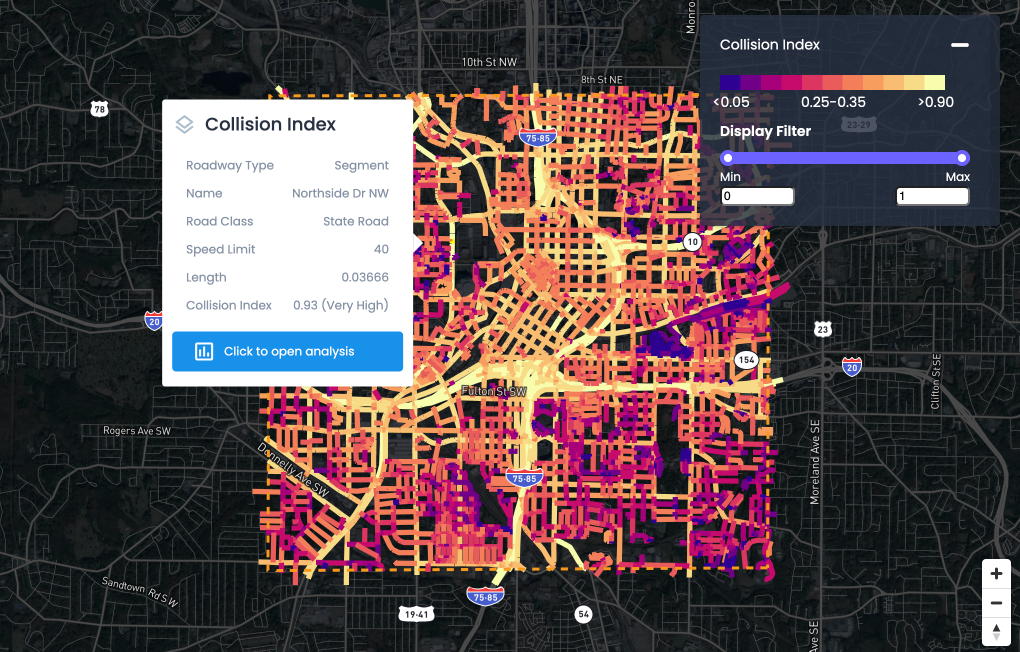

Collision Index: Proactive Traffic Safety Powered by AI

Communities now have another layer of road safety thanks to Urban SDK’s Collision Index

Customer Stories

University of Florida Transportation Institute Partners with Urban SDK to Expand I-STREET Program

Urban SDK and the University of Florida have partnered to expand the university's I-STREET Program

WEBINAR

Identify speeding and proactively enforce issues

See just how quick and easy it is to identify speeding, address complaints, and deploy officers.