Articles

EVs and the Future of Public Transit

Electric buses, electric trains, the trolley revival ... electric public transit options exist. However, before public transit can fully embrace the EV revolution some hurdles must be cleared.

Electric buses, electric trains, the trolley revival ... electric public transit options exist. However, before public transit can fully embrace the EV revolution some hurdles must be cleared.

In Richmond, Va in 1886 a young inventor and businessman, Frank Sprague, inaugurated the era of electric railways with the first practical, scalable overhead wire system.

Over the next few years streetcar systems around the world adapted and improved on his technology, as it made running vehicles less costly with fewer risks.

Before Sprague perfected his electrification system, streetcars were moved by horses, which could spook easily (and also left manure behind), or by cables pulled by enormous capstans — but which occasionally snapped, releasing huge amounts of tension and sending dangerous steel wires flying.

Third rail systems existed, but like today were limited to areas with grade-separated tracks and clear of environmental hazards.

Electric Public Transit

Electric public transit trains have been in use since the 1880s.

Their close cousins, trolleybuses, came soon after and were well-established around the world by 1910, offering a similar performance as streetcars without having to lay track.

The same era also saw an interurban craze in the United States.

There were intermediate systems between intercity rail, then still mostly powered by steam, and the streetcar system. Powered by overhead wires, interurbans ran streetcars at high speeds and with limited stops, connecting the city to nearby towns.

However, the interurban craze soon collapsed and streetcars were replaced with motorized buses.

Electric Transit to Motorized

While it’s popular to believe this was the fault of a conspiracy by General Motors and Firestone — where they bought up streetcar lines, tore up tracks, and replaced them with buses — the truth is that streetcar companies had their fares fixed before World War I and then during the Depression, towns began taxing streetcar tracks.

At the same time, cars exploded in popularity in the 1920s, competing with streetcars, slowing them, and making the streets unsafe for riders. In addition, costs were increasing, which, when combined with the fixed fares and taxation, led to conditions deteriorating.

By the end of World War II, systems had spent about 15 years without much maintenance — the streetcars were breaking down, uncomfortable, prone to derailment, and expensive to keep running.

Replacing aging streetcars with modern new buses, ripping up the tracks and trolley poles, was very attractive. Some systems did switch to trolleybuses, but motorized buses were cheaper and didn’t require the wires, so they soon became ubiquitous.

Streetcar Revival

Motorized buses continue to form the bulk of public transportation in the United States, despite an abortive streetcar revival beginning in the late 80s.

Many of these were little more than exercises in nostalgia, but a few, like the Portland Streetcar, are serious transit systems. In addition, Seattle, Los Angeles, Atlanta, Washington, DC, Miami and other cities have made large investments in light rail and subways.

In general, investments in electrified transit have lagged behind investments in highways and motorized transport.

However, this is expected to change over the next few years: the electric vehicle industry is expanding rapidly.

Electric Buses and Transit

In some cities, electric cars are becoming a common sight; manufacturers of batteries and vehicles are looking into other markets, such as buses.

Battery electric buses are already being used in some cities and there are even attempts to produce battery electric school buses.

Transit agencies largely believe that battery electric buses will be both cheaper to run and operate than trolley buses or some sort of rail system. Though this might not necessarily be the case.

While a battery electric bus would not need catenary wires, bus facilities need to be rebuilt to accommodate charging, range limitations, and time needed to recharge batteries . As a result, agencies may require extra vehicles.

Moreover, cold weather can significantly reduce the range of batteries, so many “electric” bus models have Diesel-powered heaters. As a result, choosing battery electric buses over trolleybuses may be penny-wise and pound-foolish.

A third, hybrid way exists in the form of in-motion charging technology.

In this tech, only certain portions of a route need to be wired while on-board batteries provide power when off-wire.

Public Transit's EV Future

While electric vehicle technology is making important advances, it remains expensive and, one way or another, requires extensive infrastructure investments (such as the electrical grid needing to be upgraded for widespread adoption of electric vehicles).

The limited funds of many transit agencies may ensure that mass transit’s electrification will be much slower than the ownership market.

Until costs lower and technology advances a bit more, agencies may decide they’re better served by improving service with the bus fleets they have rather than replicating poor service with advanced vehicles.

NEWS

Recent Announcements

See how public sector leaders succeed with Urban SDK.

Company News

Urban SDK Joins Government Technology’s AI Council to Help Shape the Future of AI in the Public Sector

We’re proud to announce that Urban SDK has officially joined the AI Council, part of Government Technology’s Center for Public Sector AI

Company News

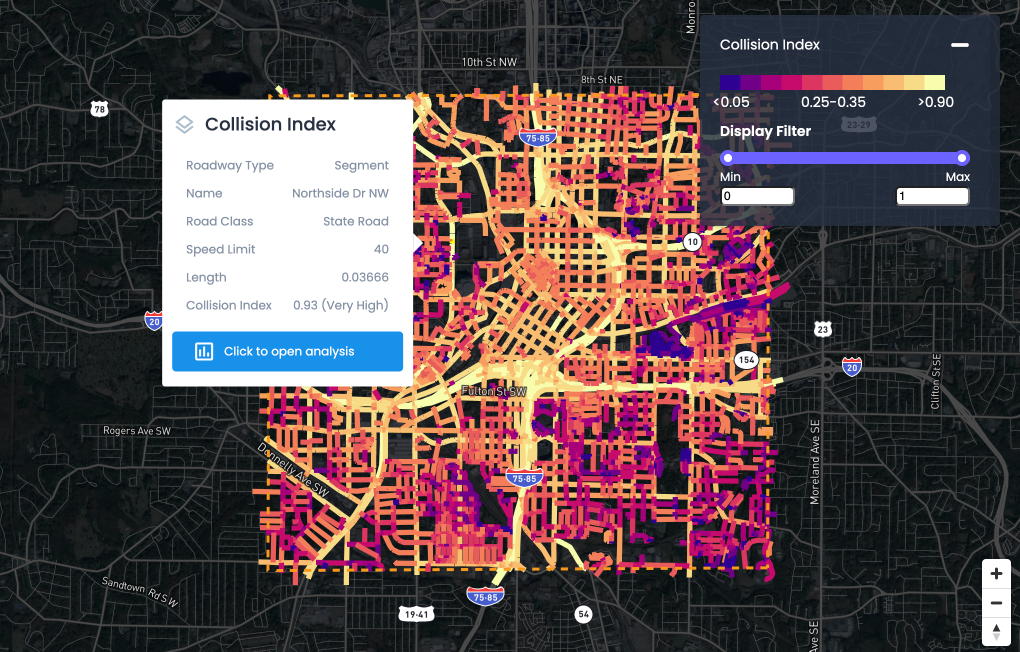

Collision Index: Proactive Traffic Safety Powered by AI

Communities now have another layer of road safety thanks to Urban SDK’s Collision Index

Customer Stories

University of Florida Transportation Institute Partners with Urban SDK to Expand I-STREET Program

Urban SDK and the University of Florida have partnered to expand the university's I-STREET Program

WEBINAR

Identify speeding and proactively enforce issues

See just how quick and easy it is to identify speeding, address complaints, and deploy officers.