Articles

The Fascinating History of Electric Vehicles

The history of electric vehicles has a long tail, dating back to battery-powered cars at the turn of the 20th century.

The history of electric vehicles has a long tail, dating back to battery-powered cars at the turn of the 20th century.

Electric vehicles have a fascinating and much older history than many people would suspect.

Not only were vehicles like streetcars and railroads electrified by the end of the 19th century, but even some cars were battery-powered — in 1900, about a third of all cars were electric, according to the United States Department of Energy. They competed with steam and various fossil fuel-powered models, but ultimately could not keep up with the advantages and development of the internal combustion engine.

Early Challenges for Electric Vehicles

Thomas Edison and Henry Ford worked on an electric car powered by Edison’s nickel-iron batteries. However, they proved unsuitable for powering cars and lead-acid batteries were too heavy.

The lead-acid ones did prove useful for equipping gasoline-powered cars with electric lights and starters, which helped make them much easier to use and was one reason why the internal combustion engine became dominant.

Batteries were the main limiting factor — they were expensive, heavy, and delivered poor performance — while gasoline was cheap (it was originally a useless by-product of petroleum refining). Also, oil companies already had distribution networks from when their main business was kerosene for lighting.

Renewed Interest in Electric Vehicles

Not much development was done on electric cars until the energy crisis of the 70s, and they continued to suffer performance and cost issues.

Designs also made them awkward-looking and easily mocked, a trend that culminated in the disastrous roll-out of the Sinclair C5 in 1985.

But things were quietly changing.

A Rise in Popularity

Research on better batteries, which began as a result of the energy crisis, continued in fits and starts as policymakers, scientists, and entrepreneurs became increasingly aware of the geopolitical dangers of fossil fuel dependency and the environmental effects of global climate change.

This resulted in a 1990 decision by the California Air Resources Board to require automakers to produce zero emissions vehicles in order to continue marketing normal internal combustion vehicles within the state of California.

In Europe, the early 2000s saw the introduction of the G-Wiz, an electric city car known for its poor safety, poor quality, and terrible looks. It was popular, though — carrying the distinction as the world's best-selling electric car until 2009.

That was also the year Tesla released the Roadster. Based on the Lotus Elise, the Roadster changed the paradigm for electric vehicles: it was fast, had decent range, and looked like a car instead of a penance.

Modern Electric Vehicle Marketplace

Today, many automakers have gotten into or returned to the electric vehicle market, such as Chevrolet and Nissan, and new startups, like Rimac and NIO, have appeared.

Ford, for example, recently introduced an electric version of the F-150, one of the best selling vehicles of all time.

Many states now offer tax credits to people who buy electric cars, a practice that is accelerating purchases. However, it has drawn criticisms from activists who note that the tax credits mainly benefit the rich.

There are also concerns that even though cars emit less from not having gas-powered engines, they still pollute through their wheels.

New Implementation and Hurdles

In the future, companies will continue to invest in developing longer lasting, quicker charging, higher capacity batteries. But they have a problem: they use toxic materials in their production, and many of the materials that aren’t toxic are hard to source metals, like nickel.

A significant portion of the world’s nickel is produced in Russia, creating a geopolitical wrinkle. Even if the nickel itself isn’t subject to current Western sanctions, they could still make it difficult for Western countries to pay for it or import it.

Charging infrastructure will continue to expand, and there will be growth in the electrification of trucking, construction, and farming equipment — cranes, bulldozers, tractors, harvesters, and so on.

Right to repair will also become a big fight, pitting mechanics, enthusiasts, and second-hand dealers against manufacturers and dealers.

Electric vehicle makers could also face renewed competition from hydrogen fuel cell-powered vehicles, something many petroleum companies are investing in. Another dark cloud, for the auto industry, is that fewer young people are getting drivers’ licenses, shrinking the future market.

Regardless of how that trend progresses, there will still be demand for electric vehicles to be used as taxis, delivery vans, food trucks, autonomous vehicles, and everything else we use vehicles for today as the world continues to move away from its reliance on fossil fuels.

NEWS

Recent Announcements

See how public sector leaders succeed with Urban SDK.

Company News

Urban SDK Joins Government Technology’s AI Council to Help Shape the Future of AI in the Public Sector

We’re proud to announce that Urban SDK has officially joined the AI Council, part of Government Technology’s Center for Public Sector AI

Company News

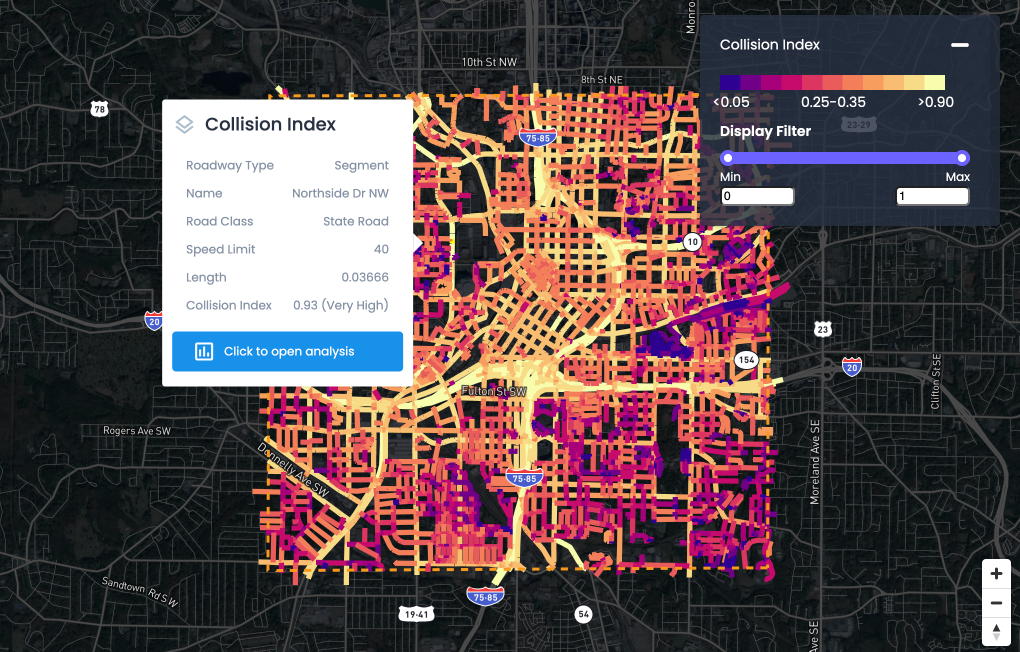

Collision Index: Proactive Traffic Safety Powered by AI

Communities now have another layer of road safety thanks to Urban SDK’s Collision Index

Customer Stories

University of Florida Transportation Institute Partners with Urban SDK to Expand I-STREET Program

Urban SDK and the University of Florida have partnered to expand the university's I-STREET Program

WEBINAR

Identify speeding and proactively enforce issues

See just how quick and easy it is to identify speeding, address complaints, and deploy officers.