Articles

Using Smart Technology to Rethink Jaywalking and Pedestrian Safety

New research and technology have state legislatures around the country reconsidering jaywalking laws.

Jaywalking was made a crime in the 1920s, but new research and technology have state legislatures around the country starting to reconsider.

Bills in several states seek to decriminalize if not repeal jaywalking laws.

Advocates have targeted them for several reasons. One is that the laws are unjust, allowing drivers to evade responsibility for hurting or even killing a pedestrian with their vehicle by enshrining victim blaming in the law.

Another reason is the growing consensus that jaywalking laws don’t make pedestrians safer. Bad urban planning, which encourages speeding and forces pedestrians to walk long distances for sanctioned crossings, makes the crossing less safe.

In 2020, vehicle miles traveled (VMT) fell to some of the lowest levels recorded as many people lived under lockdowns. Despite less driving, injuries to pedestrians and cyclists increased, likely because drivers used the nearly empty roads as speedways.

According to the Governors’ Highway Safety Association, deaths climbed to over 6700, an increase of nearly five percent, while VMT declined by around 13 percent.

In October 2021, California governor Gavin Newsom vetoed a bill decriminalizing jaywalking, despite agreeing with many activists that the laws and fines are inequitably enforced, according to the AP.

He gave no reason for the veto, but the California Sheriffs’ Association criticized the bill because while it decriminalized jaywalking, it continued to permit police officers to stop and fine pedestrians behaving in an unsafe manner.

Interpretation of the bill’s language was left unclear, law enforcement officials believed. Further, the Sheriffs’ Association said that would increase conflicts by leaving it up to the officers to decide when to act.

However, California Walks, an advocacy organization, along with 90 others, wrote a letter to Newsom in support of the bill, according to StreetsBlog.

The letter pointed out that “When the Oakland Police Department deprioritized bike and walk stops in 2019, severe pedestrian injuries and deaths dropped 11 percent.”

According to Bloomberg City Lab, jaywalking laws allow drivers and officials to ignore the harm done to pedestrians. They even enable blame to be assigned to the victims killed in crashes.

The whole concept of jaywalking is based on a successful propaganda campaign from the 1920s when the auto industry, driving enthusiasts, and the government successfully fought municipal ordinances that would have required cars to have speed governors.

It stigmatized pedestrians as “jay walkers” — a “jay” was a rural bumpkin unused to urban life — and portrayed deadly driving as the problem of a reckless minority or motorists.

By 1927 the federal Department of Commerce signed off on a model traffic ordinance that made roads, which had previously been for the public, exclusive to cars.

One of the biggest results was that roads came to be designed and engineered for the convenience of people driving, not for safety.

Speed and throughput have been the guiding principles for the last hundred years.

Many roadways are designed with wide lanes, sweeping curves and a lack of things like trees on the side to maximize visibility or provide “run-off” space for cars.

This sort of design prioritizes the safety of drivers over pedestrians and cyclists, something reflected in crash injuries and deaths.

The hierarchical street grids popular in new developments since the end of World War II are also part of the problem. They reinforce the separation of residential and commercial areas, encouraging more people to drive to their destinations, resulting in buildings having long driveways to large parking lots.

For anyone without a car, navigating such an area takes much longer, especially since things like crosswalks and stop lights are few and far between — so as not to hold up car traffic too much. Some of these areas have few street lights, only adding to the danger.

While ripe for change, redesigning street networks is a long, complex, expensive, and politically fraught process.

Fortunately, there are other ways of improving safety on dangerous stretches of road.

One way is by using machine learning to predict crashes and their locations. This technology may be just the thing to make strategic, impactful interventions to save lives.

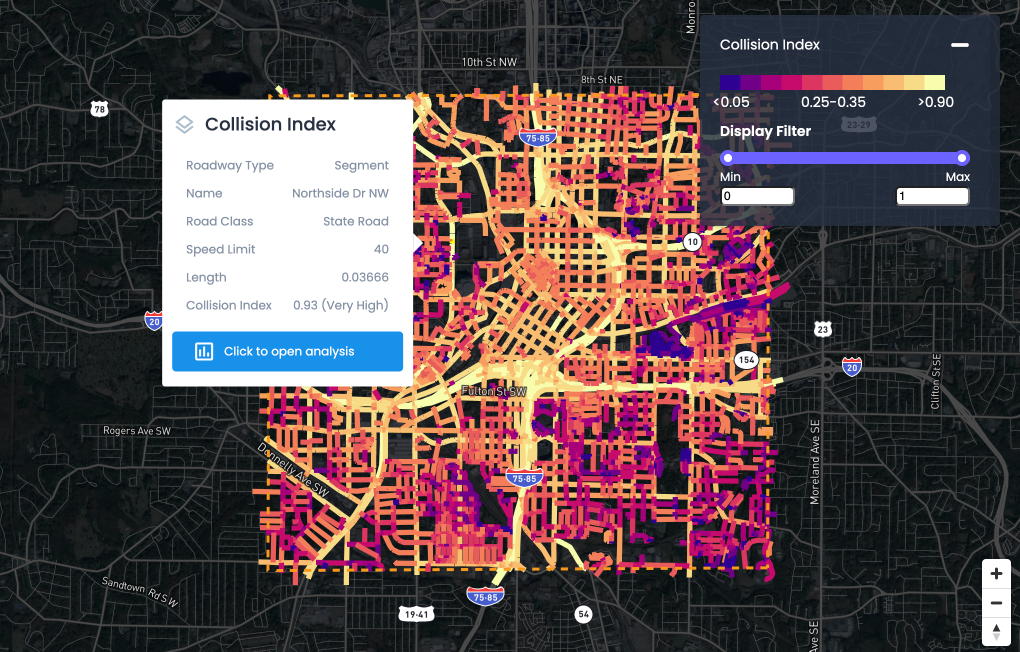

Urban SDK, for example, has used a combination of historic data and roadway geometry to build a model that predicts future crashes. We work with partners to designate safety zones for their roads, and are able to predict what days and times are most likely to have impactful crashes — crashes that dramatically impact the economy or a person’s safety.

Florida Highway Patrol officers in Jacksonville, Florida have used the model to station themselves strategically and respond more quickly to crashes or even prevent them. Likewise, Florida DOT has used it to expedite clearance times with their road rangers.

Accurate historical crash data can be difficult to find, so road safety advocates end up aware of what roads are unsafe, but not necessarily what parts are most unsafe. A predictive tool helps identify specific intersections and stretches that are most dangerous, allowing more specific changes to be made. As a result, these modifications become simpler and cheaper, and face much less opposition than redesigning an entire road all at once.

In addition to predicting where crashes will occur, another innovation may help prevent them: automated enforcement.

Automated traffic enforcement began over 20 years ago when European countries started installing speed cameras along their highways. The cameras worked a bit like an automatic radar gun, measuring the speeds of vehicles and triggering a high speed camera if one was breaking the speed limit to photograph the license plate. The plate number from the picture was then cross-referenced with the owner of the plate on file and a citation and fine would be mailed out.

Today, advances in artificial intelligence mean that computer controlled cameras can recognize, and fine, many more types of violations. In theory it’s better than sending a police officer, because it removes the potential for selective enforcement.

Technology, understanding of road safety, and the role design plays in making a street safe have all come a long way from the 1920s, when jaywalking laws were passed. They are a relic of the time of crank stars, biplanes and the popularity of plus-fours.

We can do so much better keeping pedestrians, cyclists, and drivers safe rather than arresting or fining them for crossing a street two miles from the nearest crosswalk. And smart technologies are doing their part to find more equitable solutions.

NEWS

Recent Announcements

See how public sector leaders succeed with Urban SDK.

Company News

Urban SDK Joins Government Technology’s AI Council to Help Shape the Future of AI in the Public Sector

We’re proud to announce that Urban SDK has officially joined the AI Council, part of Government Technology’s Center for Public Sector AI

Company News

Collision Index: Proactive Traffic Safety Powered by AI

Communities now have another layer of road safety thanks to Urban SDK’s Collision Index

Customer Stories

University of Florida Transportation Institute Partners with Urban SDK to Expand I-STREET Program

Urban SDK and the University of Florida have partnered to expand the university's I-STREET Program

WEBINAR

Identify speeding and proactively enforce issues

See just how quick and easy it is to identify speeding, address complaints, and deploy officers.