Articles

Sustainable Infrastructure Development

Sustainable infrastructure development hinges on recognition that land and water are finite, valuable resources.

Sustainable infrastructure development hinges on recognition that land and water are finite, valuable resources.

While it’s a grade school lesson that the United States was founded on religious freedom, it’s not too far from the truth that the country was also founded on real estate speculation.

Families like the Penns and Calverts, and the Lords Proprietors of the Carolinas, acquired rights to huge chunks of today’s East Coast and competed to settle and develop them. They often gave grants to people who could induce other people to come with them, or for services rendered. Flooding London with pamphlets extolling the virtues of a place being actively developed was a regular exercise.

By the time the US gained its independence, people like George Washington were actively involved in various enterprises aimed at settling the Ohio Valley.

Sustainable development

When it comes to developing sustainably, the important thing to know is that they’re not making land any more.

Every parcel of land has multiple possible uses, many of which preclude others — you can’t have a mine and an apple orchard on the same piece of property. Possible uses are determined by location, value, proximity to services and zoning.

The reason Midtown Manhattan has so many skyscrapers is because office space there is in such high demand, and there’s no way to build it all on the surface. Conversely, farmers in a rural Nebraska county don’t have to worry about some real estate developer pitching up one day and building a mega skyscraper; there’s just no demand for it.

This idea is often referred to as a parcel’s “highest and best use”.

Water water everywhere ...

The next important thing, after finiteness, is water.

Human activities use a lot of water — we drink it, make other beverages with it, use it to clean our goods and our bodies, and use it to transport our waste. Water makes our lawns and gardens thrive, and is used extensively in agriculture and industry.

There’s also a finite quantity on the planet that’s suitable for all those actions, and it takes time for it to be replaced.

So much water is taken out of the Colorado River, for various uses, that even in a good year it doesn’t reach the ocean anymore. Development can also impact water resources, by changing the way the land absorbs the water.

For example, asphalt paving also causes problems by covering the ground with an impermeable layer, which prevents it from absorbing water. In parts of the country with basements, this means the basement floods; in other places the water pools — the highways in Houston, for example, or a low-lying neighborhood of New Orleans.

To be sustainable, new development must minimize its consumption of land and impact on water: think the rowhouses of New York, Baltimore, and many European cities, rather than the common American form of subdivisions with houses on quarter-acre lots.

Transportation infrastructure

Another impact of development on sustainability are commutes.

Lengthy commutes pollute more and consume more fuel. There’s also a cost to each additional mile of sewer and water pipe or electrical wire.

According to Charles Marohn, the real costs of such infrastructure are the recurring maintenance costs, not the upfront, fixed costs of building it all.

Cities think they’re getting a good deal by having developers build the infrastructure and the houses, but in fact they get about 25 years of tax money from the subdivision. After that, the maintenance costs will start to exceed tax receipts, forcing the city to cut services and raise taxes, which can trigger population loss.

While this pattern of development is not economically sustainable, it’s not environmentally sustainable, either: instead of developments that can be continually adapted and reused, many are effectively disposable, allowed to decay without a thought.

Sustainable architecture

Buildings themselves can also be more sustainable.

They produce significant amounts of carbon emissions and they often represent a great deal of embodied carbon, meaning significant emissions went into making the materials.

Leaving aside issues about location or density, modern buildings are simply not designed with sustainability in mind.

A modern building with glass curtain walls is transparent to heat. In the summer it needs to be cooled constantly; in the winter it needs to be heated; in spring and fall it may need both.

Conversely, architects and businesses are working on low-energy “passive house” techniques, especially in Germany. These methods can reduce and even eliminate heating and cooling costs.

According to the United Nations, two out of every three people in the world will live in cities by 2050.

These people will need shelter and clean water wherever they live. If we can reorient our built environment to promote sustainable development, we can meet the challenge.

Learn more about how Urban SDK can help your organization make informed decisions using critical data. Contact our team here.

NEWS

Recent Announcements

See how public sector leaders succeed with Urban SDK.

Company News

Urban SDK Joins Government Technology’s AI Council to Help Shape the Future of AI in the Public Sector

We’re proud to announce that Urban SDK has officially joined the AI Council, part of Government Technology’s Center for Public Sector AI

Company News

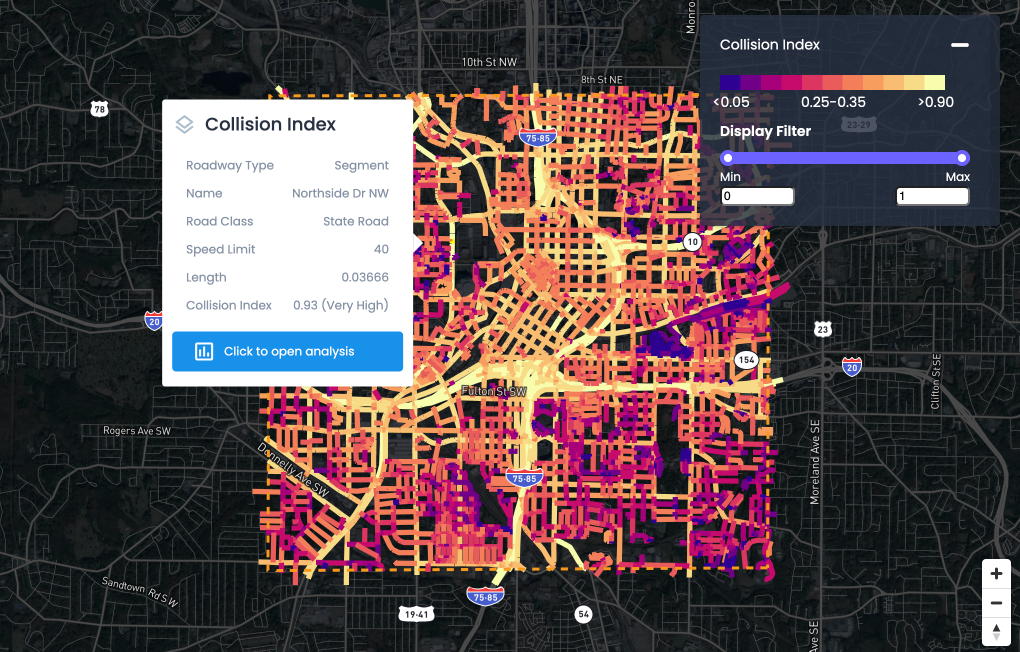

Collision Index: Proactive Traffic Safety Powered by AI

Communities now have another layer of road safety thanks to Urban SDK’s Collision Index

Customer Stories

University of Florida Transportation Institute Partners with Urban SDK to Expand I-STREET Program

Urban SDK and the University of Florida have partnered to expand the university's I-STREET Program

WEBINAR

Identify speeding and proactively enforce issues

See just how quick and easy it is to identify speeding, address complaints, and deploy officers.