Articles

The Cost of Congestion

The cost of traffic congestion on society touches everything from the environment to mental health to our pocketbooks with the supply chain. Using verified data to analyze trends and causes can mitigate it.

The cost of traffic congestion on society touches everything from the environment to mental health to our pocketbooks with the supply chain. Using verified data to analyze trends and causes can mitigate it.

Who enjoys being stuck in traffic? It’s boring, wastes time, inefficiently burns fuel, and contributes little more to society than misery and anger.

And yet, many of us put up with it day after day and year after year until it becomes an all-consuming concern — often in tandem with its stationary partner, parking.

All together, high levels of traffic congestion present an enormous set of costs to the individual driver — from time lost to stress, and ways that are easy to measure in dollars (e.g. gas consumption).

It also imposes itself on society in ways that are less easy to measure, like the costs of pollution, decreases in economic activity from having to devote so much land to parking, injuries from crashes, and road rage.

Traffic congestion represents an interesting paradox of the fact that places need a lot of people to be successful — businesses need customers, commercial landlords need tenants, restaurants need diners and so on. A downtown without people or businesses is quite eerie. However, cars carrying one or two people are pretty much the worst option for bringing large numbers of people to one place at the same time. They take up too much space and carry too few people.

A place optimized for cars can’t have enough people there to sustain itself. Unfortunately, in the United States a place not optimized for cars often likely won’t have any people because there are so few options for getting around without them.

This is to say congestion is necessary while also negative.

Daily Delay

One of the main effects of congestion is delay.

While nobody likes having a commute delayed by a traffic jam, delays can be a matter of life and death in some cases.

With so many people moving by car, the jams can delay emergency vehicles. This delays fire fighting, treatment of life-threatening injuries and responses to crime reports.

According to The Daily Texan, traffic congestion in Austin delays were costing the fire department up to a minute in response time, although the standard best time is eight minutes.

While emergency vehicles can run red and yellow lights, as well as stop signs, with their sirens blaring, drivers can not always get out of the way in a timely manner.

Delivery vehicles are also subject to costly delays — both on the micro and macro scale.

A pizza that goes cold because the driver was stuck in traffic can lead to bad reviews, affecting local business. Bad congestion can contribute to supply chain delays at grocery and hardware stores, as things take longer to deliver than previously.

Congestion and Emissions

One of the other big effects of congestion is air quality.

Most vehicles emit pollutants — ranging from carbon dioxide to dioxin — from their tail pipes.

Communities living near highways have terrible air quality and high rates of asthma — something that can be deadly in the midst of a respiratory pandemic.

In addition to air pollution, a category known as fine particulate matter can both be breathed in, causing more lung problems. It can also fall out of the air, onto the roadway, and get washed into waterways as runoff, polluting everything downstream.

The pollution that settles on the road can also be kicked backed up into the air by vehicle tires, making it even more hazardous.

In fact, some scientists believe that there is enough fine particulate matter on the roads of Britain that replacing all gas-powered cars with electric ones would not improve air quality.

Quality of Life

The third major effect of congestion is stress.

Lengthy commutes result in more sitting and sedentary behavior.

People lose sleep.

Honking raises blood pressure.

And a million other little things can go wrong on a drive to work conspire to make commuters less healthy — driving up rates of obesity, risk of diabetes, heart disease, and strokes.

Long commutes are also associated with a disinclination to socialize, which can lead to loneliness and clinical depression.

The stress and sleep loss compound all these factors, too.

So while a commute might not be a killer, most people would undoubtedly be happier and healthier without it.

Combating Traffic Congestion

The effects of traffic congestion on health, the environment, and the economy are all things that need to be mitigated by state and local governments.

But these effects need to be measured.

Traditional measures of the cost of congestion, such as those released on an annual basis by the Texas Transportation Institute for example, only measure the costs in terms of delay to drivers and the costs they pay for sitting in traffic.

They don’t measure traffic congestion's cost to society overall.

Researchers at the University of California Los Angeles argue that cities and states should adopt congestion pricing with a goal of keeping traffic free flowing on the highways.

As a performance goal, the specific prices wouldn’t matter so much, so long as the traffic continued to flow. However, planners still need ways of measuring traffic and choosing the prices.

This is an area where dynamic performance reporting and congestion management processes (CMPs) would benefit communities.

Take Jacksonville, Florida and the North Florida TPO, for example. TPO officials use Urban SDK's platform to automate more than 200 performance indicators for their CMP. This real-time reporting enables more consistent reporting and planning.

Viewed through the prism of congestion pricing, such a tool could help planners predict the effects of various price points on congestion and target the performance better.

Congestion Pricing

Congestion’s negative effects would still need to be mitigated, but the revenue raised from pricing it may be just the thing.

Tolls currently raise enough money to pay off the bond issues, and at least partially maintain the highways and bridges they are applied to; however they don’t reduce congestion.

It stands to reason that any congestion prices that would actually discourage people from driving would also raise more revenue. This revenue could be applied to improvements in public and active transportation, making mass transit work better while promoting walking and cycling as alternatives to driving.

The result would not only help reduce the pollution from congestion, but encourage people to live healthier as well.

An example or this is London. Just one year of the London congestion charge raised over 200 million pounds sterling, or around $265 million.

While at first the Covid-19 pandemic seemed like it was going to result in the evisceration of downtowns and transit systems as millions of workers shifted to permanently working from home, that has not happened.

In actuality, more trips are being taken by car, resulting in congestion at or exceeding pre-pandemic levels while transit ridership continues to fall short of normal.

This is not sustainable for road systems, transit operators, or the planet. But it lends itself for the perfect opening should organizations want to pilot congestion pricing programs.

The automobile is here to stay in America — as more electric vehicles take to the streets, this only becomes more apparent.

And while their proliferation may cut the environmental concerns of congestion, the mental health and logistics issues will remain.

The need for innovative solutions, smart regions, and dynamic reporting on the cost of congestion is greater than ever.

NEWS

Recent Announcements

See how public sector leaders succeed with Urban SDK.

Company News

Urban SDK Joins Government Technology’s AI Council to Help Shape the Future of AI in the Public Sector

We’re proud to announce that Urban SDK has officially joined the AI Council, part of Government Technology’s Center for Public Sector AI

Company News

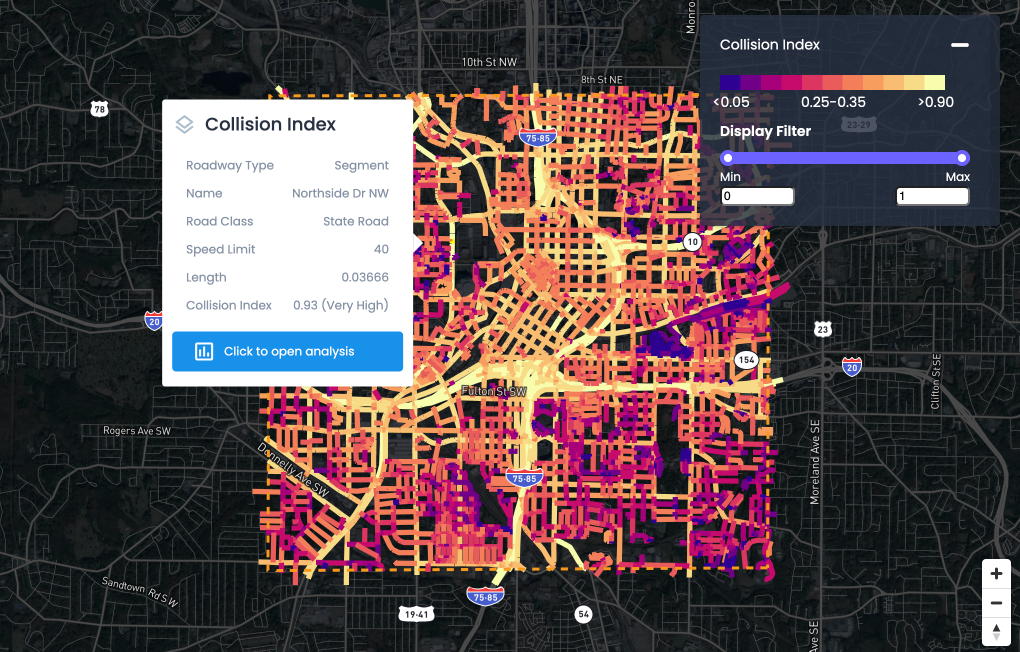

Collision Index: Proactive Traffic Safety Powered by AI

Communities now have another layer of road safety thanks to Urban SDK’s Collision Index

Customer Stories

University of Florida Transportation Institute Partners with Urban SDK to Expand I-STREET Program

Urban SDK and the University of Florida have partnered to expand the university's I-STREET Program

WEBINAR

Identify speeding and proactively enforce issues

See just how quick and easy it is to identify speeding, address complaints, and deploy officers.