Articles

Sustainability and the Challenge of Balancing Competing Needs

The concept of sustainability often comes with a complicated set of trade-offs between the environment, economy, and society.

The concept of sustainability often comes with a complicated set of trade-offs between the environment, economy, and society.

Growing up, one of my chores during the summer was to hang up and bring in the laundry. We had a dryer in the basement, next to the washing machine, but we didn’t use it often.

Instead, in the summer, and on nice days in the spring and fall, my mother and I would take the wet laundry outside and hang it up on a clothesline in the backyard to dry in the sun. After a few hours I’d go and collect it. In the winter, or when the weather was bad in the spring and fall, we had folding wooden stands in the basement to hang it on.

I think about it every time I have to put a bunch of quarters in a machine to dry my laundry, especially when its hot out. These machines use a lot of electricity and cost money, not to mention discomfort, all when sunlight and warm air are free.

The electricity that powers them must be generated somehow, and during the summer could be better used cooling people off rather than making heat. It's simple, low cost, low intensity activities like these that sustainability is made from, because at its most basic, sustainability is about doing more with less.

Environmental sustainability

The most familiar type of sustainability is environmental.

Since the energy crises in the 1970s, along with the publication of Rachel Carson’s Silent Spring a few years earlier, people have grown increasingly concerned about the environment and the way it’s affected by human activities like industry and commerce.

While today the main environmental worry is climate change, there was less awareness of it then — in the late 70s there was even a brief worry that the planet was cooling. Instead, the focus was on pollution and protecting nature.

Renewable energy was in its infancy, and so many efforts were focused on sustainability and efficiency.

Small, Japanese cars became popular and so did smaller cars from Detroit; President Jimmy Carter wore sweaters in the White House; and a nationwide 55 mph speed limit was imposed to save gas.

While energy conservation remains part of sustainability, much of the conversation today focuses on reducing impact and shortening supply chains.

It’s ultimately more sustainable to walk to a market to buy locally grown produce or locally raised meat than to save a little gas by driving a more fuel efficient car — especially since fuel efficiency runs into Jevons’ Paradox, where making a process less resource-intensive increases the consumption of the resource because more things can be done with it.

Economic and social sustainability

Economic stability, according to the University of Mary Washington, is a set of “practices that support long-term economic growth without negatively impacting social, environmental and cultural aspects of the community.”

According to Harvard Business Review, “Even those concerned about only business and not the fate of the planet recognize that the viability of business itself depends on the resources of healthy ecosystems.”

Social sustainability is the newest form of sustainability.

It seeks to build societies that are resilient to economic and environmental challenges without descending into anarchy or authoritarianism, according to the World Bank.

Both economic and social sustainability also date from the 1970s, when influential biologists like Paul Ehrlich became famous for their belief in a coming Malthusian catastrophe, where human population would out pace the available resources of the planet to maintain industrial, technological civilization.

The same energy crisis that jumpstarted the environmental movement also got people interested in economic and social sustainability. Horrific famines of the time — such as in the breakaway state of Biafra in the late '60s, Ethiopia and the Sahel in the early '70s, and Bangladesh in 1974 — also contributed to the sense of crisis.

By the 1990s, however, it had become clear that Ehrlich and others' predictions were not coming true. Famines of much of the 20th century were not caused by a lack of food any more than the oil shocks were caused by a lack of oil.

Rather, many of them resulted from wars, failed governmental policies and, chillingly, deliberate government policy — as evidenced in the Biafran famine being caused by a blockade imposed by Nigeria with the help of Britain.

Balancing competing needs

The new century has brought new challenges, or at least a heightened awareness of older challenges, that continue to make the different components of sustainability important.

We may not be on the verge of a Malthusian catastrophe, but over-exploitation of natural resources can plunge regions into crises — drought in the Middle East helped spark the Arab Spring and Syrian Civil War, leading to the European Migrant Crisis, according to Scientific American.

Complicating things is the need to balance the competing claims of each.

For example, many people believe that lithium ion batteries will be needed in huge quantities for decarbonization, both for vehicles and storing energy produced by renewable sources until needed. Yet lithium mining consumes a lot of fresh water in places that already lack it. And other battery materials, such as cobalt and nickel, are also associated with human rights abuses and environmental degradation.

Sustainability, in all its forms, is a delicate balance. One with no silver bullet solution.

There are issues that must be solved for everyone, heightened by the sense of immediacy the planet faces.

NEWS

Recent Announcements

See how public sector leaders succeed with Urban SDK.

Company News

Urban SDK Joins Government Technology’s AI Council to Help Shape the Future of AI in the Public Sector

We’re proud to announce that Urban SDK has officially joined the AI Council, part of Government Technology’s Center for Public Sector AI

Company News

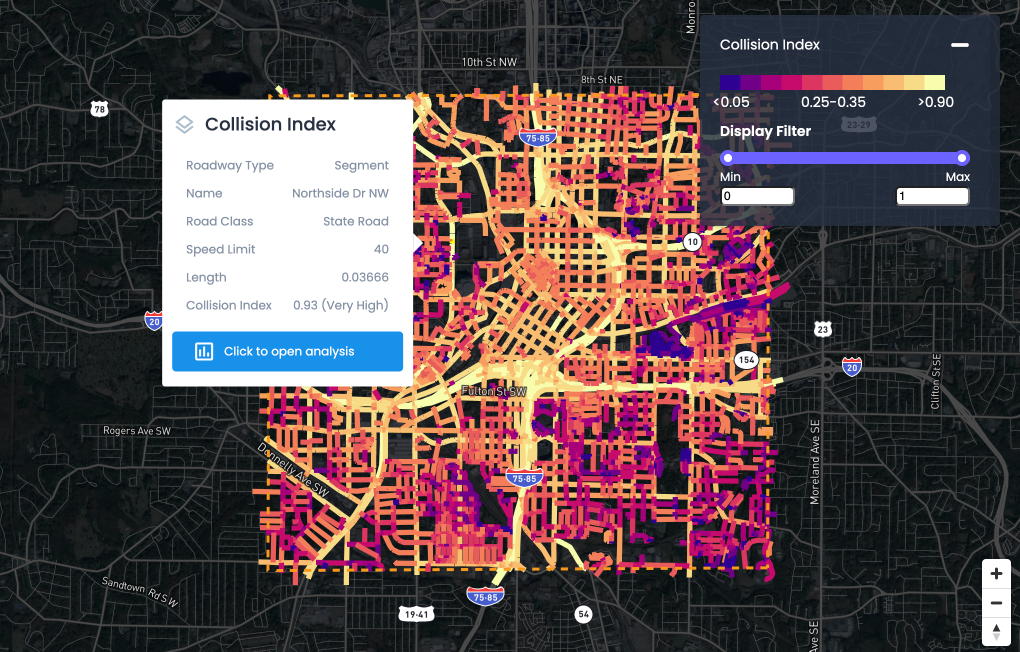

Collision Index: Proactive Traffic Safety Powered by AI

Communities now have another layer of road safety thanks to Urban SDK’s Collision Index

Customer Stories

University of Florida Transportation Institute Partners with Urban SDK to Expand I-STREET Program

Urban SDK and the University of Florida have partnered to expand the university's I-STREET Program

WEBINAR

Identify speeding and proactively enforce issues

See just how quick and easy it is to identify speeding, address complaints, and deploy officers.